Article

by Thais Gouveia

Cuddling your fears

a view on Janaina Barros' series Psychoanalysis of Cafuné*

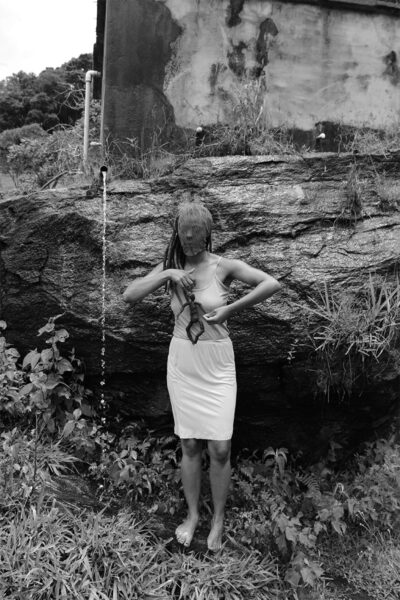

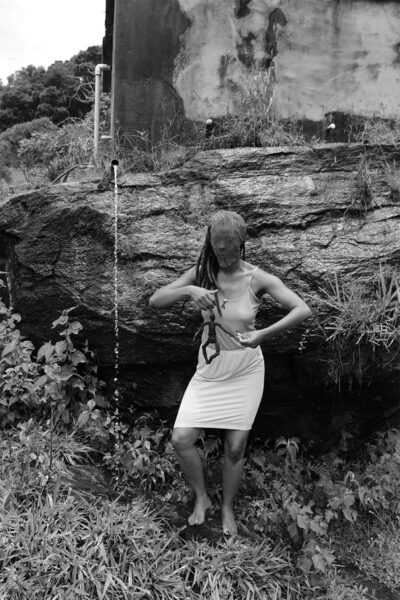

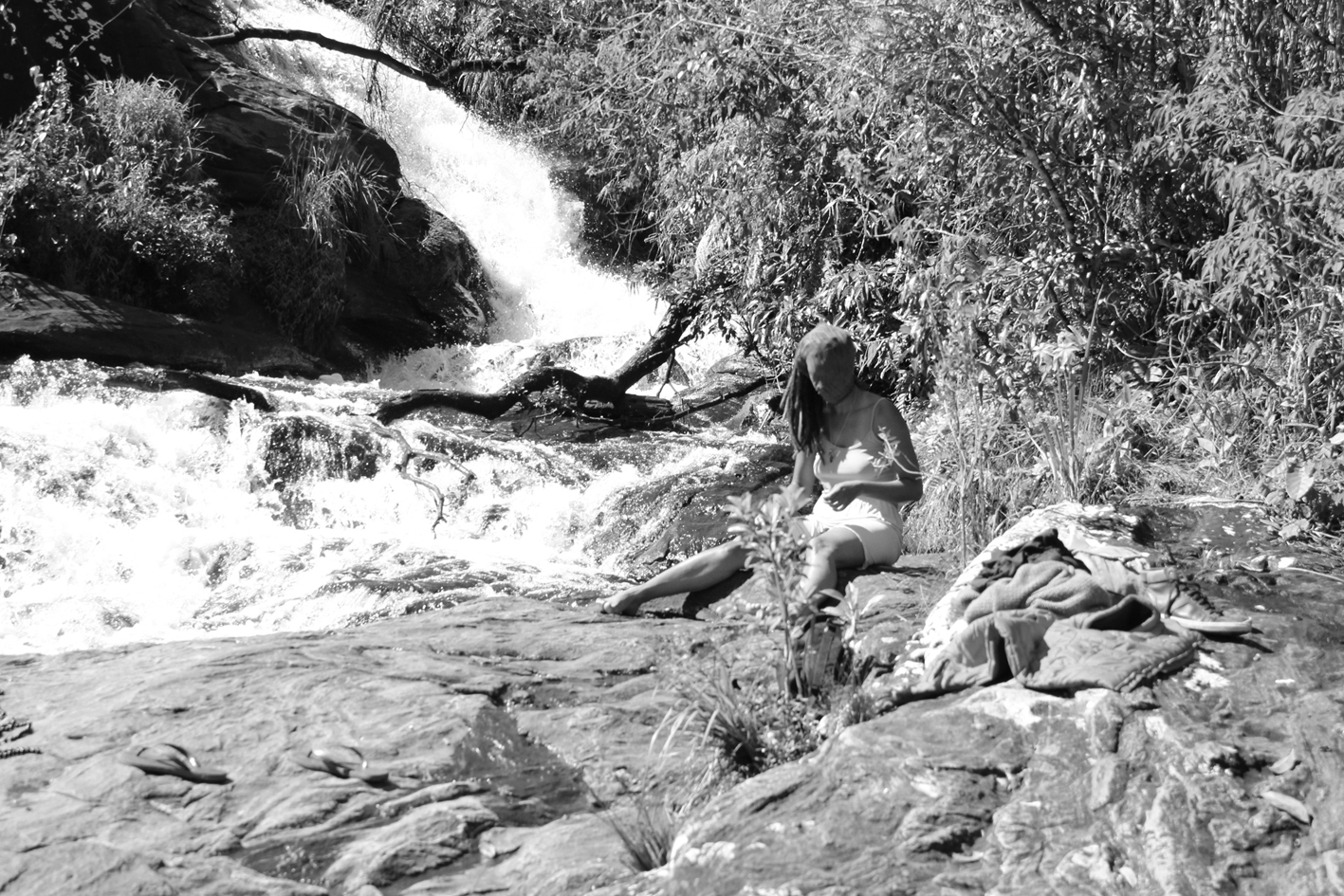

“Frequently, an act of violence does not happen in an explicit way, but masked in a alleged sweetness,” says the artist Janaina Barros. By looking at the images from the series Psychoanalysis of Cafuné: catinga de mulata (Tanacetum vulgare), 2017, produced by the artist, we can fully understand the layers of such statement. In her self portrait, the artist is barefoot, with a light and feminine vesture in the midst of nature.

She has her face covered with a kind of mesh, resembling a tinplate mask (which was put on the faces of the enslaved Africans who used to chant words of emancipation during slavery) as the image of the enslaved Anastasia, the artist plays with a puppet connected to her fingers by strings. She moves this puppet through these strings resonating with her ancestral heritage: her grandfather manufactured bamboo needles and her grandmother made knitted mesh rugs as she used to tell her granddaughter about the story of fabric, the tale behind each point until they would turn into the mould of bodies.

The title of this series refers to the essay Psychoanalysis of Cafuné – Studies of Brazilian Aesthetic Sociology (1941), by French sociologist Roger Bastide, from which the artist develops a visual research in the form of small narratives about Brazil’s colonial history as well as its stereotypes about hegemonized bodies confronting the idea of universality. This weirdness towards this university of whiteness has been following the artist from school, where she did not recognize herself in any of the textbooks.

A gap that became more and more evident throughout her life which corresponds to the very memory of slavery: this patch, this disjointed seam of silenced subjectivities, as very well explored by the artist Rosana Paulino in her solo show at Pinacoteca de São Paulo, in 2018. According to Barros, it is all about restoring self-respect and self-esteem to constitute a person’s wholeness within a historical representativeness “I understand that the way I articulate my poetry is related to the exchange of knowledge and technologies present in my family. This refers to sewing, embroidery, knitting and crochet and how it made me understand my poetic research in painting, drawing, design and artistic performance,” she says.

Visual artist, researcher and teacher, she has an admirable academic curriculum. Born in São Paulo in 1979 and currently living and working in Belo Horizonte, she has a post-doctoral degree in Information Science from the Federal University of Minas Gerais; a doctorate from the Interunits Aesthetics and Art History Post-Graduate Program at the University of São Paulo; Master of Arts from the Institute of Arts of the Universidade Estadual Paulista; specialist in Visual Languages from Santa Marcelina College, graduated in Artistic Education with a Qualification in Visual Arts from the Universidade Estadual Paulista and is currently an Adjunct Professor at the School of Fine Arts of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais.

The above paragraph dedicated to her academic life has not been put here by chance. Barros’ scientific production is inseparable from her artistic work. If we go back to the picture of Anastasia, the enslaved woman with the tinplate mask, it makes us remember that the construction of the power structure in the society is built exactly when we question: who can speak? Who speaks generates and records their knowledge from their thoughts and thus shapes their culture and their history. In this direction, Barros teams up with a group of contemporary artists and thinkers to put a spotlight on the predominance of these enunciateurs by bringing up a series of decolonial narratives that intend to raise visibility from perspectives that are not on the white Eurocentric axis.

Therefore, we have to question ourselves who is writing what we read, what is the color of their skin, what is their gender so that we can identify the asymmetries of societal inequalities that have been built up throughout the history of the coloniality of power. We have to look at the persistent segregation between white hegemonic art and black non-hegemonic art. Her doctoral thesis The Invisible Light that projects the shadow of the now, concluded in 2018, in which the artist carries out a reflection on her entire production including the Psychoanalysis series, Barros elects the definition of what the contemporary would be according to the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben as title.

What makes us contemporary beings, agents of our time? According to him, it is the ability to express one’s individuality, to speak for him/herself. This may wrongly suggest that there is harmony between this oneself and the entire scenario, as if this correspondence was flowing smoothly. In Barros’ thesis, it is perceived that this contemporaneity actually emerges from the tensions and confrontations of this contemporary subject with the mechanisms and structures of his time. In Barros’ words: “It is not possible to see the world only through the edge of a window, but to be within it with all its friction of affection and disaffection”.

It is then evident that Janaina Barros’ work emerges from an untimely concept that inhabits these contemporary fractures and in the gaze to the darkness of her time. “To perceive, in the darkness of the present, this light that strives to reach us but can not (…) To be contemporary is, above all, a question of courage: [0 be contemporary is, first and foremost, a question of courage , because it means being able not only to firmly fix your gaze on the darkness of the epoch but also perceive in this darkness a light that, while directed toward us, infinitely distances itself from us”, defines Agamben.

Barros’ poetry ultimately raises more questions than definitive interpretations. To which extent something done by others in the past impacts our present? What are our intersections? Is it necessary to be able to feel ourselves to acknowledge ourselves, as anthropologist Lilia Schwarcz recently stated, or just be able to simply contemplate a child’s drawing, as the artist did with herself with her child’s drawing as she described in her thesis, so that we can remember that sometimes it is also necessary to see things in a simple way even when there are adversities to see ahead?

*Cafuné: the act of running one’s fingers through one’s hair